-

A recipe for success on West Campus

Hospitality’s Ashley McGlauflin brings a special chemistry to West Campus

-

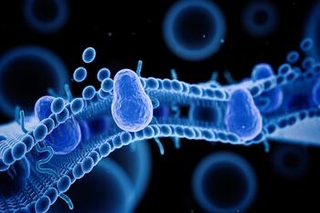

Now in 3D: Yale scientists catch Legionnaires' disease ‘in the act’

The Yale labs of Craig Roy and Jun Liu have harnessed the power of cryo-EM to solve a 30-year mystery of how the Legionella bacteria works

-

How an essential Vitamin B-derived nutrient concentrates in mitochondria

From Hongying Shen: How a key molecule is trafficked into mitochondria could provide clues for future disease treatments

-

From quantum mechanics to quantum microbes: A Yale scientist’s journey of discovery

Nikhil Mavlankar returned to his roots in quantum theory to solve a microbial mystery hidden deep in the soil

-

Giving mRNA vaccines a technological shot in the arm

The Sidi Chen lab has developed a technology to improve the power and reach of mRNA vaccines

-

Cancer's progress detailed by 3D genomic maps

New findings from Mandar Deepak Muzumdar and Siyuan (Steven) Wang could improve cancer diagnostics and lead to new therapy targets

-

Non-Antibiotic Drugs Also Disrupt the Microbiome

Non-antibiotic drugs can alter the microbiome and increase the risk of gut infections in surprising ways, a new Nature study shows

-

Mushroom-derived molecule drives microbial chemistry linked to colorectal cancer

Yale scientists reveal how different gut bacteria feed on a dietary antioxidant found in mushrooms – and a potential target for cancer therapeutics

-

A device to convert plastic waste into fuel

Engineering scientists have come together at the Yale Energy Sciences Institute to create a device to convert plastic waste into fuel

-

In Pictures: Yale Systems Biology Institute Symposium 2025

Enjoy images from the 2025 Systems Biology Institute symposium

-

Yale genome engineers expand the reach and precision of human gene editing

The Isaacs Lab at the Yale Systems Biology Institute has advanced the ability of genome engineers to edit multiple DNA sites by threefold

-

Yale-Mayo Clinic partnership uncovers genetic circuit for brain cancer

Collaboration reveals clues about the spread of brain cancer and potential for predicting patient prognosis and treatments

-

‘Help defend Yale’s teaching, research, and scholarship’

Read Yale President Maurie McInnis’ message about an increase in the endowment tax now moving through Congress.

-

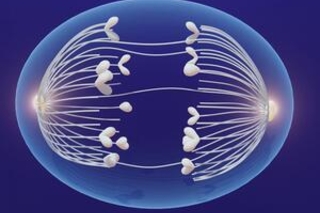

How molecular traffic cops guide development of the human brain

Collaborators at the Yale Child Study Center and Systems Biology Institute reveal molecular mechanisms that initiate brain stem cells differentiation

-

International partnership to shed new light on ancient bacteria

The Systems Biology Institute’s Michael Murrell has partnered with scholars in the UK and South Africa to uncover the driving force in cyanobacteria

-

Brudvig recognized by national academies

The Director of the Yale Energy Sciences Institute has been elected to National Academy and American Academy of Arts & Sciences

-

Stavroula Hatzios receives major award from Greek philanthropic foundation

The Yale Microbial Sciences Institute member has been honored by the Bodossaki Foundation, which recognizes distinguished scientists of Greek heritage

-

Protein turnover mapping may offer clues for Alzheimer’s, cancer treatment

The lab of Yansheng Liu has uncovered potential targets for treating Alzheimer’s disease and cancer

-

Hualiang Pi named a 2025 Searle Scholar

The Microbial Sciences Institute faculty member aims to uncover new targets to combat intestinal infections

-

Meet West Campus graduate student Rebecca Schelling

The 2nd Year Pharmacology student talked about the collaboration, community, and cutting-edge research that led her to Yale’s West Campus

-

Martina Dal Bello receives Human Frontier Science Program award for international collaboration

The Yale Microbial Sciences Institute faculty member will collaborate on a microbial science project connecting scholars in three countries

-

Microscopy pioneer Stefan Hell visits West Campus

Nobel laureate and microscopy pioneer Stefan Hell visited West Campus recently to tour the technology and innovation at the West Campus Imaging Core

-

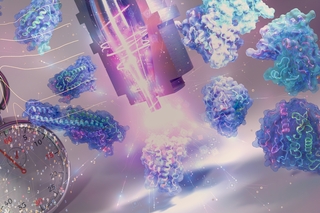

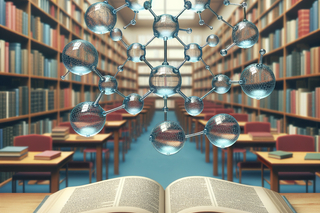

‘Molecular library’ opens up new frontier of biological space-time

A new platform from the Yale Nanobiology Institute provides access to numerous membrane proteins – key targets in the fight against resistant disease

-

Yale scientists imitate a bacterium’s eating habits to unravel common stomach bug

The findings from the Hatzios Lab could help generate new leads for therapeutic targets related to gastrointestinal diseases

-

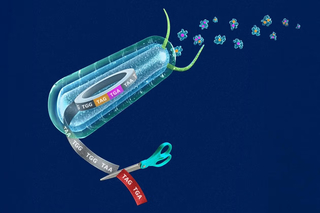

Yale scientists recode the genome for programmable synthetic proteins

Scientists at the Yale Systems Biology Institute have recoded the genome for programmable synthetic proteins

-

The hidden battle in your gut: How one bacterium outsmarts its rivals

Scientists at the Microbial Sciences Institute reveal a strategy used by microbes to stay ahead in the ‘molecular arms race’ taking place in our gut

-

Mechanical strip down helps scientists understand nerve cell signals

Scholars at the Yale Nanobiology Institute have defined the protein reactions that control our nerve cell signaling processes

-

Multi-target approach counters tumor growth in several cancers

Yale scientists have developed a treatment approach that simultaneously targets multiple immune-suppressing genes and inhibits growth in cancer

-

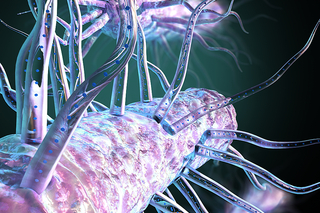

Machinery behind bacterial nanowires explained

Scientists in the Microbial Sciences Institute have identified a unique group of genes that help assemble bacterial nanowires.

-

Yale scientists decode chemical transmitter for clues to new cancer therapies

Yale Cancer Biology Institute scientists have redefined the role of a unique chemical receptor, opening the way for new targeted cancer therapies

-

Microbiologists retreat and reconnect across ‘microbial world’

Faculty, trainees and staff gathered recently for the fourth annual retreat of the Yale Microbial Sciences Institute.

-

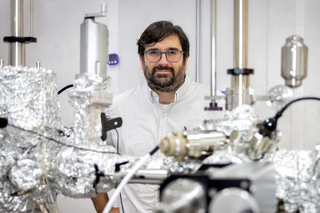

A basic science breakthrough: Evidence of a new type of superconductor

Yale physicist Eduardo H. da Silva Neto led an experiment that supports the existence of a new type of superconductor.

-

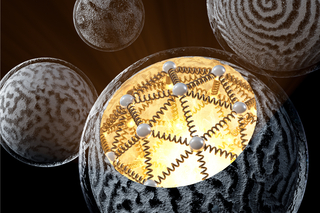

Advanced ‘mechano-biology’ sensor to target diseased cells

A team of scientists led by Julien Berro has embarked on a a project to transform the study and application of mechanical forces in cell biology

-

Molecular map shows the way towards better food choices

Developed by scientists at the Yale Microbial Sciences Institute, a new map of the molecules in our food holds promise in nurturing optimal gut health

-

Yale scientists decipher the energy patterns in our cells

The discovery offers a potential pathway to harness the energy in our cells to tackle diseases like cancer.

-

Lilian Kabeche recognized for excellence in research by an Historically Excluded Person

The American Society for Cell Biology has recognized Lilian Kabeche, faculty member at the Yale Cancer Biology Institute

-

Lilian Kabeche recognized for excellence in research by an Historically Excluded Person

The award is presented to early-career scientists who self-identify as Historically Excluded Persons

-

In pictures: systems biology unites scientists towards better health

Scientists from a kaleidoscope of disciplines gathered June 10th for the annual conference by the Yale Systems Biology Institute

-

Ken Loh receives Oak Ridge Associated Universities Award

Using tools in chemical biology, the Loh lab studies brain-body interactions at a molecular length scale.

-

Sun, sustainability, and silicon: A double dose of Yale solar fuel research

Yale chemists are combining new semiconductor materials with new molecular catalysts to create more efficient, sustainable liquid fuels

-

-

Key to harnessing light waves? First do the math

From the Miller Lab, a new mathematical model for thermal energy transfer is expected to boost next-gen energy-harvesting technologies.

-

World’s most powerful 3D super-resolution microscope arrives at Yale’s West Campus

The world’s most powerful 3D super-resolution fluorescence microscope has arrived on West Campus.

-

World’s most powerful 3D super-resolution microscope arrives at Yale’s West Campus

Yale researchers will soon watch individual molecules move through living cells, thanks to the arrival of an Abberior MINFLUX instrument, the world’s

-

Daryl Klein takes first place at Yale Life Science Pitchfest

The Associate Professor of Pharmacology was awarded for his project: Rosevix (Rosziqumab) A ROS1 Biologic for Invasive Cancers

-

For materials research, Mengxia Liu wins Packard Fellowship

For research that aims to get a better understanding of how materials behave in actual devices, Prof. Mengxia Liu has received the prestigious Packard

-

Yale scientists awaken the force in our cells

Researchers at the Yale Nanobiology Institute have developed a new tool to measure how our cells transmit physical force – a trigger for molecular mes

-

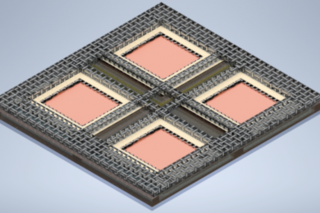

ESI’s Shu Hu will build a water-splitting device for the large-scale production of green hydrogen

With a $1.25 million award from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Prof. Shu Hu will build a water-splitting device designed for the large-scale pro

-

Hoy Shen selected as Rita Allen Foundation Scholar

Yale scientist Hongying (Hoy) Shen has been selected as a 2023 Rita Allen Foundation Scholar, it has been announced.

-

Ken Loh receives Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship Award in Neurosciences

Ken Loh has received a Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship Award in Neurosciences from the Esther A. & Joseph Klingenstein Fund and the Simons Foundation.

-

‘Strange metal’ sends quantum researchers in circles

A Yale-led team of physicists has discovered a circular pattern in the movement of electrons in a group of quantum materials known as “strange metals.

-

Hoy Shen selected as Rita Allen Foundation Scholar

When activated, a protein found in cells that line the body’s tissues can inhibit viral spread — offering the potential for a new defense against COVI

-

-

Yale scientists develop ‘MAJESTIC’ solution for future cancer cell therapies

Scientists at Yale have developed a new gene delivery and immune cell engineering technology with the potential to advance cell therapies for cancer a

-

Yale scientists receive $10.5M for ‘team science’ exploration of membrane proteins in their natural environment

An interdisciplinary team of Yale scientists are coming together to address crucial questions…

-

Multi-tasking protein has potential to protect against disease

Our bodies reproduce trillions of new cells in order to grow and develop.

-

Chemical ‘supercharger’ solves molecular membrane mystery

Assemblies of tiny molecular proteins span the membranes that encapsulate our cells, directing cellular activities and regulating the transport of mat

-

At Yale’s West Campus, a youth movement in science communication

Yale research scientist is on a mission to make the subject more appealing to young people - and so far, the data suggests it’s working.

-

Atrouli Chatterjee selected as 2023 Optica Ambassador

Atrouli Chatterjee, a Postdoctoral Associate in the Yale Nanobiology Institute, has been selected as a 2023 ‘Optica Ambassador’ - one of ten exception

-

Decoding the cell signals between young proteins and their ‘chaperones’

Of the 25,000 different proteins in the human body, insulin, antibodies, and collagen are among the few that perform their biological jobs by literall

-

Meet the Undergrads at West Campus: Mikayla Osumah

Next in our series highlighting undergraduate students at Yale’s West Campus is Mikayla Osumah in the Institute of Biomolecular Design and Discovery!

-

Yale scientists ‘spray paint’ cells to reveal secret genes

Many of the thousands of proteins that help our cells grow and function remain undiscovered, especially the tiniest ones…

-

Trainees ramp up plans to reconnect at Yale’s West Campus

In the fall of 2021, Caroline Brown, Zheng Wei, and Iman Mousavi took on the task of coordinating the West Campus Student and Postdoc Committee during